Museum admission is $12 per adult, $10 for veterans & seniors and $7 for students

Special Exhibits

Ronald E. Rosser

Left: Director Warren Motts with Advisory Board Member, Medal Of Honor recipient, Ronald Rosser.

On January 12, 1952, a very cold day, Corporal Ronald E. Rosser, of the U.S. Army’s 38th Infantry, 2nd Infantry Division, was holding nothing more harmful than a radio, acting as a communications “pointer”. As Love Company started up Star Hill in the Iron Triangle in the vicinity of Ponggilli, Korea, a burst of machine gun fire betrayed an enemy ambush. Hearing a voice say, “Let’s go,” he dropped the radio, grabbed his carbine and a fistful of grenades. Ron Rosser was about to enter the history books.

Charging ahead of the rest and diving into a trench, Ron quickly killed two of the enemy, one with a shot in the head, the other in the chest. It was just the beginning, as he realized that the trench was filled with members of an enemy group that just 11 months ago had killed his brother Richard. Five more of the enemy were dead in minutes. Hurling a grenade into a bunker, he shot two more Reds as they came out.

Now out of ammunition, Rosser ran back to resupply ammunition and grenades. Returning to the front, he led charges on two more bunkers. With friends falling all around him, he fought on until out of ammunition again. A third time he would charge up the slopes of Star Hill, until, on that single day of action, Ron Rosser had single-handedly killed 13 of the enemy. Though wounded, Rosser spent the rest of the battle retrieving wounded friends from between the lines.

General Orders No. 67, dated July 7, 1952, awarded Ron Rosser the Medal Of Honor. See Medal of Honor Citations for the full citation and listing of other recipients. It was presented to him by President Harry S. Truman at the White House.

Ron ended his military career as a Master Sergeant. He is one of two Ohio residents still living to have received the Medal Of Honor in the state of Ohio.

Motts Military Museum is proud to have Ron Rosser serving on its Advisory Board.

General Paul W. Tibbits JR

Career Highlights

Awards Gen. Tibbets earned during his distinguished 32 year military career.

This is the first time this list has ever been published.

- Command Pilot-Wings

- Distinguished Flying Cross with One Oak Leaf Cluster

- Distinguished Service Cross

- Purple Heart

- Air Medal with Three Oak Leaf Clusters

- Joint Service Commendation Medal

- Air Force Outstanding Unit Award

- Distinguished Unit Award

- American Defense Service Medal

- American Campaign Medal

- Europe-Africa-Middle East-Campaign Medal with Three Battle Stars

- Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with Two Battle Stars

- World War II Victory Medal

- National Defense Service Medal with One Battle Star

- Air Force Longevity Service Award with One Silver Loop

- Joint Staff ID Badge

Until his death in November 2007, at the age of 92, the Motts Military Museum was honored to have General Paul W. Tibbets Jr. as a member of our Advisory Board.

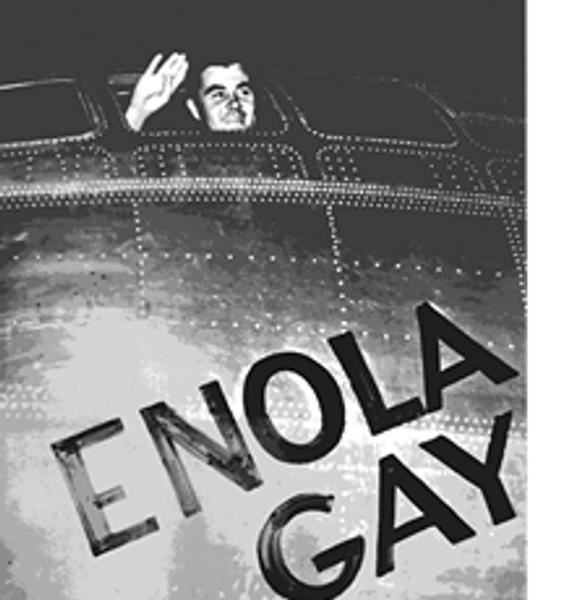

General Tibbets will be remembered for piloting the Enola Gay, the B-29 "Superfortress" that dropped the first atomic bomb ever used in combat.

He was a loyal supporter and was always willing to help us with fund raising events.

The Motts Military Museum displays the largest collection of Gen. Tibbets memorabilia including his full dress blue Air Force Brigadier General uniform and much more.

Paul Tibbets was born in Quincy, IL., on February 13, 1915. He lived in Iowa and moved to Miami, FL. at the age of 9. At 12, he had his first airplane ride. It was to drop Baby Ruth candy bars at a carnival to the crowd below. With this job, his love for flying was born and would last a lifetime.At the age of 13 he went to the Western Military Academy in Alton, IL. He attended the University of Florida in 1933. While there, he took flying lessons at the Gainsville Airport.

He then went to the University of Cincinnati Medical College, with the expectation of carrying on the family tradition of medical doctors. But, his love for flying became number one in his life. He spent all of his spare time and money taking flying lessons.

He left medical school in 1937 and joined the Army Air Corp. at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio. Here he could fly at government expense.

While stationed at Ft. Benning, GA., and being a shotgun enthusiast, he was assigned to the base Skeet Shooting range. This is where he met George Patton. They became good friends and spent many hours on the shooting range. He also served as Patton’s pilot during tank range maneuvers. He has some great stories to tell about him.

Paul flew B-10 and B-12 aircraft in low flying exercises. Returning from one of these missions in December 1941, he heard on his aircraft radio that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. America was at war.

He was then transferred to the 29th Bomb Group to fly the new B-17. He temporarily flew the B-18 on anti-sub duty off the U.S. east coast. He was made Commander of the 40th Squadron, 97th Bombardment Group (Heavy) at MacDill Air Base, Tampa, FL. He trained his crew in the B-17 and flew many hours, day and night. Most of this time, he slept in his clothes.

From Bangor, Maine, he flew across the North Atlantic to England. This was the first group of American-manned, tactical aircraft to reach the United Kingdom in WWII.

Paul was made the Executive Officer of the 97th Bombardment Group (Heavy). On August 17, 1942, he flew the first American plane on a daylight bombing raid over German occupied Europe. The mission was to bomb a rail yard in France. This mission was flown in the aircraft named, “Butcher Shop”, not his regular plane. His future missions were flown in the “Red Gremlin”. Paul had a great attachment to this aircraft and called it, “the Good Gremlin”.

He flew many missions over German occupied territory. On one of these missions he was wounded but was able to return to his base.

Before the invasion of North Africa he flew General Mark Clark on a secret mission to Gibraltar. It was from Gibraltar that General Mark Clark directed the invasion of North Africa, “Operation Torch”.

He later flew General Eisenhower (sitting on a 2 x 4) to North Africa on an inspection tour. Paul flew many missions in North Africa during 1942-43. He was then moved to Algiers and continued to fly missions.

General Doolittle sent Paul back to the states to help develop a new bomber, the B-29. After extensive training with the B-29, he was sent to Colorado Springs where he was selected to lead a top secret mission. He was 29 years old at the time. He would command the 509th Composite Group. From the Island of Tinian, Paul Tibbets would go down in history as the first pilot to drop the Atomic Bomb — the target, Hiroshima.

After the war he was consulted frequently about atomic testing and in the late 1940’s and 50’s he worked very hard to promote the new B-47 Jet Bomber.

in 1954:

he was a member of the NATO staff in Paris. Later Paul was put in charge of the 308th Bomb Wing in Savannah, GA.

in 1959

he was promoted to Brigadier General and was put in command of the Air Division at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, FL.

in 1962

he was selected to put together the National Military Command Center in Washington DC, at the Pentagon.

in 1964

he went to India to operate the Military Assistance Group, and in 1969, after this very impressive career, he retired from the military service.

in 1976

Paul was appointed president of Executive Jet Aviation, now Net Jets, with world headquarters in Columbus, Ohio, a position he held until his retirement.

Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker

Additional Information

The Motts Military Museum, with the tireless efforts of Richard Hoerle is proud to present, on our museum grounds, a historically accurate, “Replica” of the boyhood home of Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker. With the help of our many volunteers, generous patriotic individuals and corporations, the construction of this, full scale replica was made possible.

With the help of the “Capt. Eddie” family, we have furnished the interior of the house as it was when Capt. Eddie lived there. With various “Capt Eddie” memorabilia displayed throughout the house, we believe this will assist the educational process for future generations about the life and times of this American patriot.

_______________________________________

When World War One started, Eddie Rickenbacker was 26 years old, too old to enter flight training. Eddie Rickenbacker wanted to fly. He went to France, learned to fly, became an officer and was assigned to the 94th Aero Squadron, becoming its commanding officer. He became an American “Ace of Aces” with 26 aerial victories. Eddie was also the recipient of the Medal Of Honor for action in France. On September 25, 1918, on a voluntary patrol, he discovered 7 enemy planes. He attacked against those odds and shot down 2 enemy planes.

After the war, Capt. Eddie traveled on lecture tours and produced the Rickenbacker automobile until 1928. In 1927 he purchased the Indianapolis 500 Motor Speedway, and sold it in 1945 to the present owners. In 1934, Eddie became the General Manager of Eastern Airlines. He retired as its CEO in 1963.

Until he died in 1973, he lectured and toured as a true patriot of the United States of America.

Eddie Rickenbacker's childhood home

From 1895 to 1922, this was the Columbus, Ohio, home of famed World War I aviator Edward “Eddie” Vernon Rickenbacke. Eddie, a leading race car driver prior to World War I, joined the American Expeditionary Force as a sergeant and staff driver in 1917. He sailed to France the next month with John J. Pershing and his staff. Although overage and not a high school graduate, Rickenbacker, with the assistance of William “Billy” Mitchell, received an assignment to flight school.

After 17 days at the French aviation school at Tours, Eddie received his wings and a commission as first lieutenant; however, he was assigned to the Advanced Flight School at Issoudun as an engineering officer, not a pilot. Eventually he was transferred to the 94th Aero Pursuit Squadron, where on April 14, 1918, he took part in the “first combat mission ever ordered by an American commander of an American squadron of American pilots.”

Rickenbacker became commander of the squadron on September 24. The next day he single-handedly took on seven German planes over the German lines and shot down two of them—an act for which he was belatedly awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1930. In six months he shot down 26 German aircraft—22 airplanes and four balloons.

Eddie Rickenbacker returned home after the end of the war as the idol of the American public, the “American Ace of Aces.” He refused offers to make movies or endorse products, but he did publish his war memoir entitled Fighting the Flying Circus. He married Adelaide F. Durrant in 1922 and founded the Rickenbacker Motor Company, which went bankrupt in 1927. Eddie then joined General Motors where he worked in both their automobile and aircraft divisions, before a venture of several years to build his own brand of Rickenbacker automobiles.

In 1938 he purchased Eastern Airlines from General Motors, making it the “first airline to operate without a subsidy from the Federal government.” During World War II Rickenbacker toured American bases at home and abroad as a special civilian consultant for Secretary of War Henry Stimson. On one of these tours to the South Pacific, Eddie’s airplane became lost, ran out of fuel and had to land in the ocean. His book Seven Came Through describes the 24 days he and the crew spent adrift on life rafts before being found.

After the war, Rickenbacker returned to Eastern Airlines as Chairman of the Board, a position he held until his retirement in 1963 at age 73. In October 1972 Eddie Rickenbacker suffered a stroke, and he died in Zurich on July 24, 1973. Courtesy of National Park Service

In 1974, Lockbourne AFB, just several miles from our museum, was renamed Rickenbacker AFB.

Tuskegee Airmen

The Tuskegee Airmen were an elite group of African-American pilots in the 1940s.

They were pioneers in equality and integration of the Armed Forces. The term “Tuskegee Airmen” refers to all who were involved in the Army Air Corps program to train African Americans to fly and maintain combat aircraft. The Tuskegee Airmen included pilots, navigators, bombardiers, maintenance and support staff, instructors, and all the personnel who kept the planes in the air.

The primary flight training for these aviators took place at the Division of Aeronautics of Tuskegee Institute. Air Corps officials built a separate facility at Tuskegee Army Air Field to train these black pilots. The Tuskegee Airmen not only battled enemies during wartime but also fought against racism and segregation, thus proving they were just as good as any other pilot. Racism was common during World War II, and many people did not want blacks to become pilots. They trained in overcrowded classrooms and airstrips, and suffered from the racist attitude of some military officials. The Tuskegee Airmen suffered many hardships, but they proved themselves to be world class pilots.

Even though the Tuskegee Airmen proved their worth as military pilots they were still forced to operate in segregated units and did not fight alongside their white countrymen. The men earned the nickname “Red Tail Angels” since the bombers considered their escorts “angels” and the red paint on the propeller and tail of their planes.

By the end of the war, 992 men had graduated from Negro Air Corps pilot training at Tuskegee; 450 were sent overseas for combat assignment. During the same period, about 150 lost their lives while in training or on combat flights, and 32 were held as POWs by the Nazis. These black Airmen managed to destroy or damage over 409 German airplanes, 950 ground units, and sank a battleship destroyer. They ran more than 200 bomber escort missions during World War II.

Yet, these same men returned to the US only to face continued discrimination. After the war the size of the armed forces was drastically reduced, and many of the Tuskegee Airmen returned to civilian life. But the war did not bring an end to the policy of segregation, and the Tuskegee Airmen who remained in uniform continued to serve in all-black flying units. Tuskegee Army Air Field was closed in 1946 and all the segregated flying units were concentrated at Lockbourne Air Base (just a few miles from our museum) in the 477th Composite Group, an all black unit with a squadron of P-47 fighters and another of B-25 bombers. The base remained segregated from March of 1946 until July of 1949, nearly a year after president Truman officially integrated the military.

Capt. Harold Sawyer

Capt Harold Sawyer, P-51 pilot in WWII

Capt Harold Sawyer, P-51 pilot in WWII

Capt Harold Sawyer, P-51 pilot in WWII

One of our long-time board members until his death on 22 June 2002, Captain Harold Sawyer, was one of these valiant trail-blazers who shot down two Nazi planes in 1944 while flying his P-51 from a base in Italy. He was very active during the early years of our museum, and we are proud of him and his many contributions.

Capt Harold Sawyer, P-51 pilot in WWII

Capt Harold Sawyer, P-51 pilot in WWII

Pilot Capt. Harold E. Sawyer being awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross by Col. Noel F. Parrish, December 5, 1944 for extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial fight against the enemy in the Mediterranean Theater of Operation in WWII.

Lt. John H. Rosemond

Lt. John H. Rosemond, 1943–45 Tuskegee Airman

Lt. John H. Rosemond, 1943–45 Tuskegee Airman

Lt. John H. Rosemond, 1943–45 Tuskegee Airman

John H. Rosemond was a Tuskegee Airman and served as a navigator/bombardier in B-25 bombers during WWII. Following the war, he graduated in 1951 as a medical doctor from Howard University in Washington DC. He opened a successful family practice in Columbus and in 1969 he became the first black man elected to Columbus city council. He served three four-year terms and was nominated as the first black man to run for mayor of Columbus in 1975.

Although he was defeated, he remained very influential with many boards and organizations until his death in 1991 at the age of 74. In 1996 he was posthumously inducted into the Ohio Veterans Hall of Fame. Our museum proudly displays his aviation flight jacket and his class photograph from WWII, donated by his widow, Rosie.

Lt. John H. Rosemond, 1943–45 Tuskegee Airman

Lt. John H. Rosemond, 1943–45 Tuskegee Airman

Aviation flight jacket worn by Lt. John H. Rosemond.

9/11 Artifacts

FDNY Engine Arrives in Groveport, Emotions Run High

Reporter: Joe Stoll | Web Producer: Ken Hines

Posted: Friday, August 31 2012, 07:35 PM EDT

GROVEPORT — A fire truck, crushed during the collapse of the World Trade Center towers, arrived in central Ohio Friday morning.

A semi-truck hauled F.D.N.Y. Ladder 18 to Motts Military Museum in Groveport.

Dozens gathered to welcome the artifact, including Karen Russelo, who lost her son, U.S. Army Spc. Vincent James “V.J.” Pomante III, to an Improvised Explosive Device in 2006 in Iraq.

“There’s still many of our soldiers out there. I lost my son as a result, and we need to bring the rest of them home safe,” Russelo said.

It took Warren Motts 8 months, and significant donations, to get this big addition for his 9/11 collection at the museum, which includes police cars from Ground Zero, a piece of the World Trade Center, and an antenna.

“I really felt that this would be the capping glory of the whole thing because it encompasses the entire action that took place at Ground Zero,” Motts said.

During the ceremony, Congressman Steve Stivers spoke to the crowd, and told the story behind this special fire truck, named Fort Pitts. Stivers said the truck was at the base of the second tower when it collapsed. Fire crews hid under it to protect themselves from the falling debris. Stivers said none of the Engine Company 18’s crew were killed because they used the trucks as shields.

“We had firemen and policemen, not running away from danger, but running into, and this is an incredible symbol of the job they do everyday to protect our lives,” Rep. Stivers said.

Warren Motts will show the 9/11 fire truck every Thursday at 10:00 a.m.

Check out this video from the 2021 Columbus Dispatch Home & Garden Show.

Copyright © 2021 Motts Military Museum Inc - All Rights Reserved.

Website Powered by MechanUX

Weather Closure

Due to the severe incliment weather expect to hit us in Central Ohio this weekend, we will be closing the museum through Wednesday, Jan 28th, 2026. We look forward to seeing you after this weather passes, during our normal hours of operation. Please stay warm and safe!